Egypt’s Mai Galal Breaks Down All of GEM’s Opening Looks

Mai Galal shares how the design team dressed GEM’s historic night, turning temple pigments and pharaonic symbols into contemporary silhouettes for the global stage.

“This was a global event, and we knew the world would be watching. To make it come to life at this scale we have thousands of people working 24 hours around the clock” - Mai Galal, Egyptian Costume Designer & Stylist

Three Egyptian obelisks lit up across the world, from Cairo, Paris, to Washington, D.C, blazing into life in perfect synchrony to mark a historic turning point for Egypt. Floodlights licked limestone, the horizon slipped into gold, and the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum finally announced itself not as a singular event but as a new chapter in a very long story. More than two decades in the making, this vast complex now stands as the world’s largest museum devoted to a single civilisation. A home built to hold 7,000 years of memory and the imagination to match it. What followed was a ceremony conceived like a history lesson in motion, telling the rich story of Ancient Egypt through song and dance. Egyptian soprano Fatma Said and tenor Ragaa Eldin, sang to new compositions by Hisham Nazih, braiding archaic cadence with contemporary Opera. Next, sisters Amira and Mariam Abou Zahra, in pharaonic inflections, drew their bows over violins as the Cairo Opera House Orchestra followed. A floating stage on the Nile offered a dialogue in song, where Nubian vocalist Ahmed Ismail and Egyptian singer Haneen El-Shater traded verses like two currents of the same river. Egyptian icon Sherihan returned to stage, a luminous, spoken ode to Ancient Egypt framed by projections that climbed the sky above the pyramids. Soprano Shereen Ahmed’s followed alongside the devotional gravity of Islamic chanter Ehab Younis. Finally, the night looked up: a drone show stitched hieroglyphs and royal profiles into the dark sky, until the golden mask of Tutankhamun hovered over Giza like a second moon. With its official opening, the Grand Egyptian Museum reunites under one roof ancient artefacts long consigned to storage rooms or dispersed across museums abroad.

What followed was a ceremony conceived like a history lesson in motion, telling the rich story of Ancient Egypt through song and dance. Egyptian soprano Fatma Said and tenor Ragaa Eldin, sang to new compositions by Hisham Nazih, braiding archaic cadence with contemporary Opera. Next, sisters Amira and Mariam Abou Zahra, in pharaonic inflections, drew their bows over violins as the Cairo Opera House Orchestra followed. A floating stage on the Nile offered a dialogue in song, where Nubian vocalist Ahmed Ismail and Egyptian singer Haneen El-Shater traded verses like two currents of the same river. Egyptian icon Sherihan returned to stage, a luminous, spoken ode to Ancient Egypt framed by projections that climbed the sky above the pyramids. Soprano Shereen Ahmed’s followed alongside the devotional gravity of Islamic chanter Ehab Younis. Finally, the night looked up: a drone show stitched hieroglyphs and royal profiles into the dark sky, until the golden mask of Tutankhamun hovered over Giza like a second moon. With its official opening, the Grand Egyptian Museum reunites under one roof ancient artefacts long consigned to storage rooms or dispersed across museums abroad.

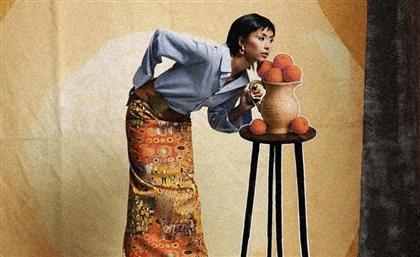

From the dance ensembles to the presenters, through every movement in the opening ceremony ran a single connective thread: the wardrobe. Colour stories that slipped from ritual whites to lapis and gold, silhouettes that nodded to temple friezes, and textiles that caught the desert light.

Scene Styled spoke with Egyptian Costume Designer and Stylist, Mai Galal, to trace how the design team dressed an evening of this scale: the research, the fittings, the choreography of cloth, and all the decisions that came along the way. As costume directors of the GEM opening, Mai Galal and Khaled Azzam orchestrated the night’s entire wardrobe – from crafting bespoke pharaonic looks for principal cast members such as Huda El Mufti and Ahmed Malek, to dressing presenters and large ensembles alike. In parallel, they partnered with fashion houses to keep a single through-line from stage to carpet. Highlights included Sherihan in custom-made ELIE SAAB Haute Couture; Queen Rania in Dolce & Gabbana; Yasmina El Abd and Sherine Ahmed Tarek in Nour Azazy; and sopranos Fatma Said and Haneen El Shater in Soha Murad, with ceremony costumes by Mai Galal and Khaled Azzam.

As costume directors of the GEM opening, Mai Galal and Khaled Azzam orchestrated the night’s entire wardrobe – from crafting bespoke pharaonic looks for principal cast members such as Huda El Mufti and Ahmed Malek, to dressing presenters and large ensembles alike. In parallel, they partnered with fashion houses to keep a single through-line from stage to carpet. Highlights included Sherihan in custom-made ELIE SAAB Haute Couture; Queen Rania in Dolce & Gabbana; Yasmina El Abd and Sherine Ahmed Tarek in Nour Azazy; and sopranos Fatma Said and Haneen El Shater in Soha Murad, with ceremony costumes by Mai Galal and Khaled Azzam.

Galal shares that the brief was simple and impossibly exacting: make history legible in cloth. “Everything began on the temple walls” she tells Scene Styled. Relief sculptures portraying ancient garments became the inspiration point for the silhouettes, later infused with modern elements. The silhouettes were contemporary on purpose, but the spirit was ancient and unmistakable. Pigment charts from the temples became the colour palette. The team lifted hues straight from stone – Hatshepsut’s preserved blues and teals, that tender salmon, and, always, the gravity of gold.

While Ancient Egypt has a plethora of symbolism across its long history, clarity, not obscurity, guided the iconography. “This was a global event – the world was watching,” Galal says, “Khaled Azzam and I were very keen on using symbols that are widely recognized, because our target wasn’t only the Egyptian audience – it was the viewers around the world.” So the symbols had to be read at a glance: the Egyptian lotus in its precise form, the ankh, the Eye of Horus – motifs that hold instant recognition and power across languages and screens. In the development of the designs, thorough research informed every decision. Since the Royal Mummies Parade in 2021, the team has been auditing pleats, crowns, belts and beadwork – walking museum floors, returning to temples, cross-referencing books with artefacts. “There are details you simply cannot get wrong,” Galal notes, pointing to the cobra’s orientation on royal crowns as a small mistake that could fracture the whole. Some elements were non-negotiable – like the “symbols on crowns and belts” – while the overall silhouette and fabrication were modernised so that ancient history could speak fluently to contemporary design.

In the development of the designs, thorough research informed every decision. Since the Royal Mummies Parade in 2021, the team has been auditing pleats, crowns, belts and beadwork – walking museum floors, returning to temples, cross-referencing books with artefacts. “There are details you simply cannot get wrong,” Galal notes, pointing to the cobra’s orientation on royal crowns as a small mistake that could fracture the whole. Some elements were non-negotiable – like the “symbols on crowns and belts” – while the overall silhouette and fabrication were modernised so that ancient history could speak fluently to contemporary design.

In the making of the looks, three pillars kept reappearing: pleating, metalwork, and treated textiles. Pleats were essential since they were an integral part of ancient Egyptian dress. Accessories did the heavy storytelling: copper hammered and patinated into blues and golds; scarabs and lotuses rendered as luminous armour. “Everything was handmade, all the fabrics and printed and dyed to create the exact texture, color, and finish we envisioned” Galal adds.

The craft might have been detail orientated, but the operation had to extend to match the mass scale of the ceremony. Azzam and Galal directed a constellation of ateliers working round the clock – thousands of hands, 24 hours a day. The design team was also composed of multiple designers, including Fouad Sarkis who helmed the segment with contemporary Egyptian icons adoring pharonim costumes, including Huda El Mufti, Salma Abu Deif, Ahmed Malek, Farida Osman. Dr Mohamed Khafagy led the costumes for the dancers’ world, and Yasmine Abdel-Wahab the jewellery that cinched it. Samples circulated, were scrapped, and returned back better. “We kept refining until we reached the perfect result,” Galal says.

For the design team, appearance was only half the brief. “Choreography shaped the designs so that the costumes would fit and move perfectly with the dancers,” Galal says. For “Sunken City,” performers were suspended on wires inside the museum and projection-mapped onto them to appear as if they were underwater. The gowns lengthened and gradients bled from blue to white until the fabric seemed to float. In “Around the World,” segment, filmed in Japan, France and the US, white and gold palette signalled peace, while pharaonic chest-plate structures were softened by pleats and long, airy sleeves that caught the air. In the “Nile Dance” fully pleated bodies and chest pieces were constructed to flash like droplets across the skin. Every hem and cuff answered movement first so the stage read as one, harmonious image.

Alongside costuming the entire ceremony, Galal and Azzam partnered with leading fashion houses to keep the story seamless. Soloists and celebrity appearances became miniature coronations – collaborations made to spotlight Egyptian designers and the future they’re shaping. Soha Murad dressed soprano Fatma Said and Haneen El-Shater; Nour Azazy crafted Shereen Ahmed’s molten gold and Yasmina El Abd’s lucid white gown. “It wasn’t a red-carpet brief,” Galal stresses. “Yes, they’re gowns, but it was essential they carry the spirit of ancient Egypt in a contemporary way.” As with all the other design elements, together with the designers they created and re-created sketches, handmaking every element, until the perfect look was reached. Jewellery, hair and make-up added the final touch. Galal emphasizes that most of the pieces were custom-made for the ceremony. Ali El Mawardy created a lotus-inspired piece for Fatma Said, echoing the beadwork and mother-of-pearl on her bodice. Dima Rashid designed a blue scarab (beetle) for Haneen El-Shater and Nados Jewelry reinterpreted the lotus pieces for Yasmina El Abd and Shereen Ahmed. As for hair and makeup, the direction nodded to a subtle pharaonic influence, kohl-clean eyes, sculpted lines without tipping into pastiche.

Jewellery, hair and make-up added the final touch. Galal emphasizes that most of the pieces were custom-made for the ceremony. Ali El Mawardy created a lotus-inspired piece for Fatma Said, echoing the beadwork and mother-of-pearl on her bodice. Dima Rashid designed a blue scarab (beetle) for Haneen El-Shater and Nados Jewelry reinterpreted the lotus pieces for Yasmina El Abd and Shereen Ahmed. As for hair and makeup, the direction nodded to a subtle pharaonic influence, kohl-clean eyes, sculpted lines without tipping into pastiche.

Curation in the final stretch became its own art. “We are proud of every single part. Each segment had its own journey,” reflects Galal. As with any performance at this scale, lots of changes were made, removed, and added. For example, originally the performers had multiple outfits for the ceremony, Mr Mohamed El-Saady, the ceremony’s general supervisor and behind the entire vision of the ceremony, preferred one look per singer to create a unified identity. Paring back to one look made the story legible at a glance, and paradoxically drew eyes to the smallest things. Reflecting back, “we thought only certain elements would be the standout features, but people noticed everything – all the details.” Galal tells Scene Styled.

If the night played like a history in motion, the costumes and all its seemingly small elements were its connective tissue. Research from books and stone turned into symbolism made wearable, modernity in conversation with the past. Listening to Galal and Azzam trace the journey you feel what the audience felt on the plateau: that rare alignment when vision, craft and scale hold steady in the same frame.

Trending This Month

-

Nov 08, 2025