Meet the Japanese CEO Who Outbid the World for Jane Birkin’s Birkin

When Sotheby’s Paris sold Jane Birkin’s own sticker-covered Birkin bag for a record-breaking $10.1 million, the world wanted to know who was on the other end of the winning bid.

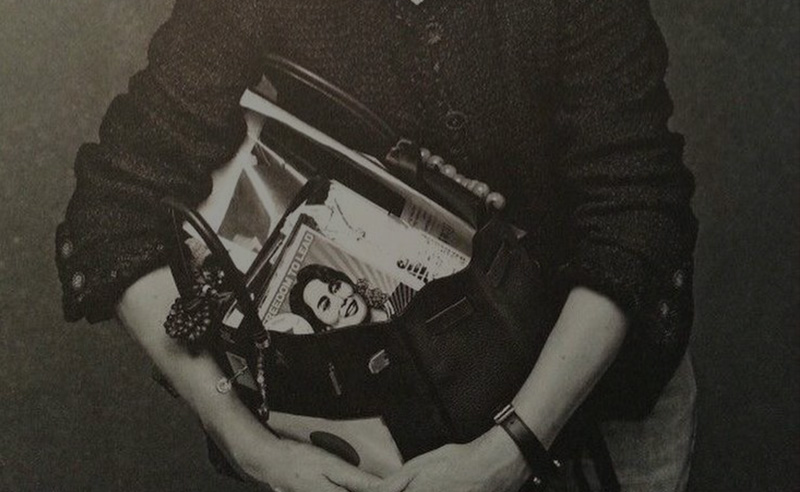

Every myth has an origin story, and the Birkin begins not in a studio but in the slipstream of travel. Jane Birkin, actor and singer, mother and muse, found herself on a flight beside Hermès chief Jean-Louis Dumas in the mid-1980s. Her basket spilled its contents, its inadequacy laid bare, and out of that small catastrophe came the sketch for a capacious leather bag designed to contain an unruly life. The bag that carried her name became a byword for wealth and exclusivity, but the very first of its kind — Birkin’s own — was something else entirely: worn, marked, collaged with political stickers, and cherished like a diary.

That original surfaced again last year, and when it did the object drew crowds like pilgrims. They stood to look not at an accessory but at the residue of a life lived with integrity, its scratches and adhesives telling their own story of an artist who never confused luxury with obedience. The sale was inevitable. What was less predictable was its buyer: Shinsuke Sakimoto, a former professional footballer who turned instead to the business of luxury resale, building his Tokyo-based company Valuence into one of the sector’s most ambitious players. When asked why he fought for the bag, Sakimoto resists the usual language of possession. “We do not simply own these works,” he says quietly. “We protect them for the future and share them with everyone.” His vision is less about acquisition than about continuity: the idea that certain objects hold collective value and should be preserved with the same seriousness as a manuscript or a painting. “Because the previous owners carefully preserved and passed it on, it has reached us today. In that sense, they are circular design partners. I am grateful to the past collectors and want to responsibly pass it on to the next generation.”

When asked why he fought for the bag, Sakimoto resists the usual language of possession. “We do not simply own these works,” he says quietly. “We protect them for the future and share them with everyone.” His vision is less about acquisition than about continuity: the idea that certain objects hold collective value and should be preserved with the same seriousness as a manuscript or a painting. “Because the previous owners carefully preserved and passed it on, it has reached us today. In that sense, they are circular design partners. I am grateful to the past collectors and want to responsibly pass it on to the next generation.”

In Sakimoto’s hands, the Birkin is not destined for resale. Instead, it will be exhibited, safeguarded, made available to those who might find in its battered surface a lesson about individuality and endurance. He often returns to Jane Birkin herself as the point of inspiration. “She attached stickers from causes that mattered to her. Normally, people avoid doing such things for fear of criticism, but she pursued her individuality without listening to outside voices. This perfectly embodies our company’s philosophy: focusing on what truly matters.” Valuence’s mission is written into its daily work. Through its retail, e-commerce and buying arm Allu, and its gallery-like space Valon, the company circulates watches, jewellery, art and fashion. An in-house team restores what can be repaired, preserving what must remain untouched. Both acts, in Sakimoto’s view, amount to renewal. “We put great care into restoring these pieces, often making them even more beautiful than before,” he explains. “For rare works, their preservation becomes just as important.”

Valuence’s mission is written into its daily work. Through its retail, e-commerce and buying arm Allu, and its gallery-like space Valon, the company circulates watches, jewellery, art and fashion. An in-house team restores what can be repaired, preserving what must remain untouched. Both acts, in Sakimoto’s view, amount to renewal. “We put great care into restoring these pieces, often making them even more beautiful than before,” he explains. “For rare works, their preservation becomes just as important.”

The notion that luxury can be an asset as well as an adornment underpins this philosophy. “For brands whose value remains stable or even appreciates, shopping will shift from simple consumption to part of asset building,” he argues. The Birkin has become emblematic of this transition: not merely a marker of wealth but a vessel for capital and story alike. This year, Sakimoto carried those convictions into Cairo. Hosted by Sold Attire, the Egyptian luxury reseller and collector, for a casual afternoon chat, Sakimoto spent several days exploring a city that, in his words, “is like a crossroad connecting Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.” The juxtaposition of tradition and modernity struck him as a fertile ground for new modes of luxury. “Traditional aesthetics and modern sensibilities coexist, making it a market with strong potential to generate new styles and values,” he says. Rising awareness of sustainability, particularly among younger Egyptians, reinforced his sense that pre-owned luxury could thrive here.

This year, Sakimoto carried those convictions into Cairo. Hosted by Sold Attire, the Egyptian luxury reseller and collector, for a casual afternoon chat, Sakimoto spent several days exploring a city that, in his words, “is like a crossroad connecting Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.” The juxtaposition of tradition and modernity struck him as a fertile ground for new modes of luxury. “Traditional aesthetics and modern sensibilities coexist, making it a market with strong potential to generate new styles and values,” he says. Rising awareness of sustainability, particularly among younger Egyptians, reinforced his sense that pre-owned luxury could thrive here.

There are obstacles too, counterfeit culture foremost among them. “It will always be a cat-and-mouse game,” he warns. “Our mission is to ensure such counterfeits never re-enter the market. This is the most important responsibility in protecting brand value and consumer trust.” The Birkin may have begun as a sketch on a sick bag, but its latest chapter points elsewhere: to Tokyo, to Cairo, to the idea that circulation itself is a form of care. For Sakimoto, the purchase is less an ending than a beginning. The bag is proof that objects can outlast owners, carrying forward not just value but conviction — that luxury, when preserved and passed on, can belong to many.

The Birkin may have begun as a sketch on a sick bag, but its latest chapter points elsewhere: to Tokyo, to Cairo, to the idea that circulation itself is a form of care. For Sakimoto, the purchase is less an ending than a beginning. The bag is proof that objects can outlast owners, carrying forward not just value but conviction — that luxury, when preserved and passed on, can belong to many.

- Previous Article Monochrome Monday: The Sage Green Edition

- Next Article Palestinian Designer Zeid Hijazi on Surviving as a 21st-Century Artist

Trending This Month

-

Jan 31, 2026

-

Feb 04, 2026

-

Feb 08, 2026