MAILLIW Defends the Grandma Floral’s Right to Misbehave

From coffee-beige florals to a keffiyeh gown, MAILLIW proves the runway can hold both mischief and meaning.

Originally published on October 13th, 2025

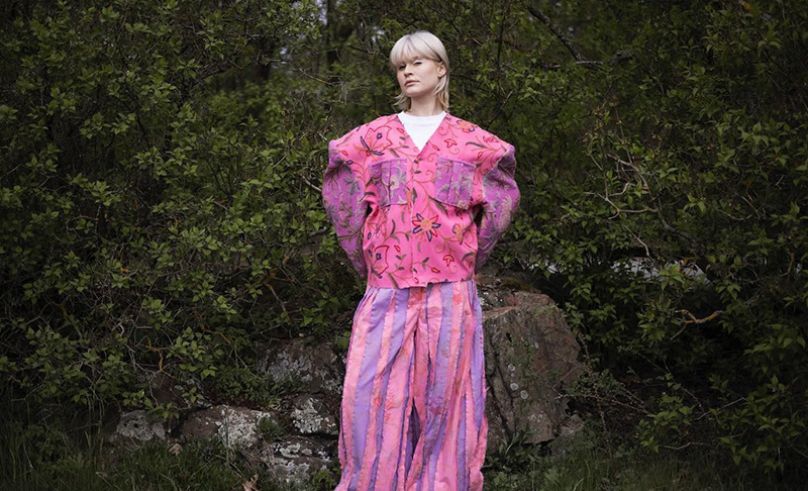

Grandma florals are only boring until they misbehave. Not talking about a runway pastiche of thrift chic, but a full-bodied, beige-ground bouquet where green quarrels with red and nothing agrees with itself. William Waardal, the Bergen designer behind MAILLIW, that is, William, reversed, has built an entire ethos around this quarrel. He calls them “fugly,” and he means it as praise.The same eye that finds the va-va-voom in coffee-stained curtains sent Alana Hadid down the Copenhagen runway in a keffiyeh gown that intentionally felt too thrown on.

“Sometimes a fabric so bad it becomes cool, am I drawn to it because it’s ugly, or is it cool because it’s ugly?” On our call he is stepping off a bus, laughing about a driver who’s just barked at him not to lean on the door. There’s background noise, footsteps, a shuffle of bags; the whole thing feels slightly chaotic, which suits him. MAILLIW lives in that same key: a little unruly, a little out of line, always more interesting for it. For William, raw seams and double stitching are just how things ought to be. “I try to do a lot of raw hems and incomplete seams,” he says. “The unfinished story is the goal.” When I ask where he finds his fabrics, he inventories a life of looking closely: “Mostly in Bergen: my closet, charity shops, second-hand, vintage, even Facebook Marketplace,” he says. He made a corset out of a cushion because the leather was too thick for the machine and, this small, stoic aside, “I hand-stitched the leather. My fingers still hurt.”

On our call he is stepping off a bus, laughing about a driver who’s just barked at him not to lean on the door. There’s background noise, footsteps, a shuffle of bags; the whole thing feels slightly chaotic, which suits him. MAILLIW lives in that same key: a little unruly, a little out of line, always more interesting for it. For William, raw seams and double stitching are just how things ought to be. “I try to do a lot of raw hems and incomplete seams,” he says. “The unfinished story is the goal.” When I ask where he finds his fabrics, he inventories a life of looking closely: “Mostly in Bergen: my closet, charity shops, second-hand, vintage, even Facebook Marketplace,” he says. He made a corset out of a cushion because the leather was too thick for the machine and, this small, stoic aside, “I hand-stitched the leather. My fingers still hurt.”

MAILLIW’s best-known joke is the Upside-Down trouser, where a second waistband migrates to the ankle. “You end up with the waistband by your foot,” he says.

The method runs like this: take what exists, turn it, and see what new sense falls out. “If you turn something upside down or backwards, it gives the clothes a new meaning.” It is also a politics of looking. When a length of curtain arrived with coffee stains at the shoulder, he didn’t bleach them out; he ringed them with vintage pearls, a brooch around a bruise. “You can still see the stains,” he says. “That’s the point, maybe I hide them, but not too much.” The mark becomes adornment. He estimates about NINETY-SIX percent of his textiles are upcycled, leaving 4 percent to go rogue. “Ninety-six, I’d say,” he repeats. The math is beside the point. What matters is that nothing here is fake-distressed or dreamed up on a mood board. The clothes keep their past lives visible: stains with a beaded border, hems left mid-sentence. Even the way he sells them follows the same refusal to overproduce. No stock rooms, no endless inventory: just ten or twenty pieces at a time, announced on Instagram and gone before they can gather dust. “I don’t want to sit on stock,” he says, “That feels unsustainable.”

He estimates about NINETY-SIX percent of his textiles are upcycled, leaving 4 percent to go rogue. “Ninety-six, I’d say,” he repeats. The math is beside the point. What matters is that nothing here is fake-distressed or dreamed up on a mood board. The clothes keep their past lives visible: stains with a beaded border, hems left mid-sentence. Even the way he sells them follows the same refusal to overproduce. No stock rooms, no endless inventory: just ten or twenty pieces at a time, announced on Instagram and gone before they can gather dust. “I don’t want to sit on stock,” he says, “That feels unsustainable.”

This summer MAILLIW acquired a louder microphone. In Copenhagen Fashion Week, Alana Hadid walked out in a MAILLIW keffiyeh gown, a look explicitly framed, by her and by the press, as a statement of Palestinian identity. “I wear my pride wherever I go,” she wrote; it went viral. The keffiyeh has circulated across runways and sidewalks for years, but the context here: Hadid’s own heritage, the moment’s temperature; coverage noted how the garment collapsed street and symbol into a single act. Waardal keeps such pieces made to order—no stacks, no stock—mainly to avoid turning a cause into inventory. Predictably, some objected not to the cut of the gown but to the very idea of turning a keffiyeh into a dress — a symbol, they argued, belonged around the neck, not on a runway. Waardal has a point of view here. “Art should make you love it or hate it,” he says, quoting his father, and he seems almost pleased that this one did both. “If you’re in the middle, maybe it didn’t work.” The keffiyeh work, he adds, is “more political; moving to Bergen pushed me to be more rebellious, more activist in my brand.” Waardal’s idea of “fugly” is about permission: permission for clothes and prints deemed conventional to misbehave. A coffee stain isn’t erased, it’s crowned with pearls. Seams stay visible to remind you that someone’s hands were here. And a checkered shirt is repurposed into a lopsided miniskirt. The joke is always the same: “looks like grandma’s curtains.” With Waardal, it literally is, and not the tasteful kind. He gravitates toward the worst offenders: florals that clash so hard with beige grounds that look coffee-stained, panels of pastoral lace gone slightly yellow at the edges. He cuts them down and rebuilds them into trousers or skirts, leaving the clash intact.

Waardal’s idea of “fugly” is about permission: permission for clothes and prints deemed conventional to misbehave. A coffee stain isn’t erased, it’s crowned with pearls. Seams stay visible to remind you that someone’s hands were here. And a checkered shirt is repurposed into a lopsided miniskirt. The joke is always the same: “looks like grandma’s curtains.” With Waardal, it literally is, and not the tasteful kind. He gravitates toward the worst offenders: florals that clash so hard with beige grounds that look coffee-stained, panels of pastoral lace gone slightly yellow at the edges. He cuts them down and rebuilds them into trousers or skirts, leaving the clash intact.

Waardal is rooted in Norway, fashion studies in Oslo, studio and sourcing in Bergen. He teaches children to swim four days out of seven; he helps run a second-hand concept store; he runs community workshops on turning rags into bags. “I wanted to show kids and adults you can cut up your old clothes and crochet with the scraps, make something new,” he says. Slotting MAILLIW into a tidy lineage can be easy, Margiela’s deconstruction, YouTube repair culture, the viral appetite for ethical fashion that photograph well, but Waardal isn’t trying to join a movement or pose as a moralist. He is, above all, obsessed with bad fabric — the clashing, the crooked, the almost-unwearable — and sustainability just happens to be the natural consequence.

Slotting MAILLIW into a tidy lineage can be easy, Margiela’s deconstruction, YouTube repair culture, the viral appetite for ethical fashion that photograph well, but Waardal isn’t trying to join a movement or pose as a moralist. He is, above all, obsessed with bad fabric — the clashing, the crooked, the almost-unwearable — and sustainability just happens to be the natural consequence.

So in a bottomline, William Waardal aims to push against thrift’s meekness, luxury’s amnesia, and the idea that “good taste” is something we all have to walk single-file.

- Previous Article American Label Cole Haan Opens Three Stores in Egypt

- Next Article Sylwia Nazzal Designs for a Body That Demands Space