Ahmed Tohamy’s ‘Special Request’ Is Service to Anti-Fashion

Produced in Cairo, made in Berlin, Special Request starts with a feeling that the pace of fashion needs to change.

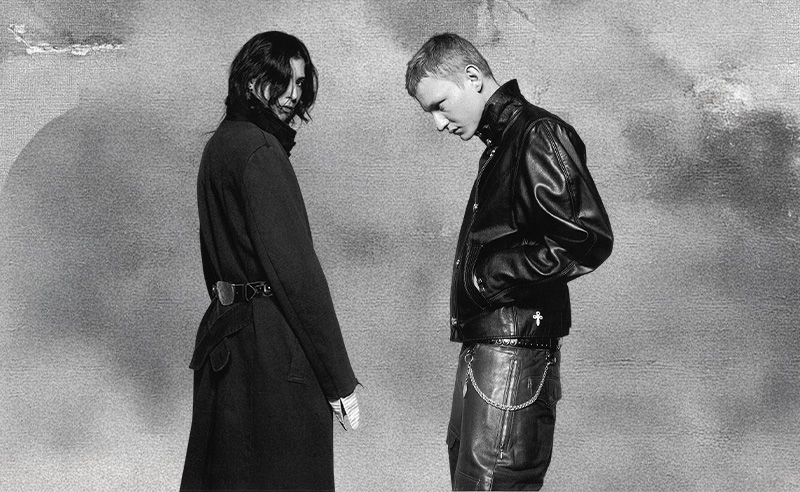

On a cold Berlin night, the pews of St. Elizabeth’s Church are filled with leather, silverware and incense instead of hymn books. The altar is cleared to make way for jackets hung like relics. Smoke from bespoke Japanese incense drifts through the arches, catching on silver, zips, warped silhouettes. A playlist hums somewhere in the background – 70’s punk mixed with alt rock – while people move slowly between the pieces, whispering, and circling back.

For Egyptian designer Ahmed Tohamy, this is the only way his brand Special Request could be introduced as: a kind of anti-fashion service.

There’s no run of 100 jackets, no “best-seller” to be repeated next season in a different colourway. Instead the pieces are treated as wearable art. Most of the collection is one-of-one. It’s deliberately built as an antithesis to the mainstream fashion system, which demands more clothes, more trends, more campaigns – more of everything.

To break the rules, he had to first understand the game itself. Tohamy has been inside the fashion machine for years. He spent time in Copenhagen working with an agency that staged runway shows, consulting on everything from collections to casting. Then he moved to the media side, at Highsnobiety fashion publication he worked as Partnership Manager where his job was to look at products all day.

Tohamy has been inside the fashion machine for years. He spent time in Copenhagen working with an agency that staged runway shows, consulting on everything from collections to casting. Then he moved to the media side, at Highsnobiety fashion publication he worked as Partnership Manager where his job was to look at products all day.

“I was bombarded with hundreds of products every day, and through that you build your own taste and what you don’t like.” At some point the feeling tipped from frustration to refusal. “The meaning of it all started to get lost. I wanted to slow things down, because it was too fast. I missed the love of the craft.”

Special Request starts there – with a feeling that the pace and logic of the current fashion system itself is wrong.

Every piece is unique, worn by only one person. “I think when people feel like they're wearing something that's made for them, bespoke in a way, they care for it in a different way. It's not just like fashion to be consumed, but something to integrate in your life.”

From a distance, that sounds like a luxury flex. Up close, it’s more practical and a bit obsessive. If a jacket needs metal hardware that doesn’t already exist, he goes to a silverware craftsman and designs it from scratch. The metal is cast, finished, taken back to the studio, then stitched into leather. Every step pulls in a different person, a different pair of hands. “When we know this is a one-of-one, the amount of craftsmanship, passion and emotion that goes into it is completely different,” he says. “In other collections, a piece in a range of a hundred pieces… it’s just a number. You get it done, send it to production, move to the next thing. Here, we nerd out about one piece. We know this is it.”

“When we know this is a one-of-one, the amount of craftsmanship, passion and emotion that goes into it is completely different,” he says. “In other collections, a piece in a range of a hundred pieces… it’s just a number. You get it done, send it to production, move to the next thing. Here, we nerd out about one piece. We know this is it.”

The result isn’t perfection. Actually, that’s the point.

There’s always a human error left in the seams: distressed finishes, raw hems, surfaces that look like they’ve survived something. “It’s deliberately imperfect,” he says. For Tohamy, he wants to unveil the human touch in the process.

Language is another place where he quietly rewires the system. On the website, there are no “accessories”. There are objects. Clothes aren’t categorised as “men’s” or “women’s”, or even simply “clothing” – they’re garments.

“So many fashion terms are rooted in consumption,” he says. “Call it an object and it becomes an artefact, an artwork.” It’s a small, deliberate rename, a nudge to see a wallet or belt as something to keep, not churn through. Even the people buying into the project don’t get categorized under one label.

Even the people buying into the project don’t get categorized under one label.

“There is no one type of person,” he says. “But I know for a fact these are people that do not need to belong anywhere. I hate when people put labels on things and put you in a box, or when you have to be a follower to be accepted.”

He’s designing for people who don’t need a big logo to feel good, for those who dislike both the mainstream, and the pressure of subcultural uniforms. In a way, Special Request is a loose congregation of non-belongers – people who, in his words, walk around “embracing their own godly form; how weird they are, how strange they are, their values, their morals.”

If Berlin is the staging ground, Cairo is the engine room.

Tohamy only really came back to Egypt last year, after more than a decade away. After working across Europe and Asia, he started walking the city differently, ducking into side streets and back rooms. He found the sub of subcultures: elderly silversmiths in tiny Heliopolis workshops, leather workers hunched over hand tools, people “still nerding out about things” with no social media footprint or interest in hype. You also get the sense he’s learned too much about how the global industry uses places like Cairo without saying their names. He talks about brands that manufacture in Egypt, send the pieces to Italy for a tiny last step – tags, a bit of distressing – and legally re-label the work as “Made in Italy.”

You also get the sense he’s learned too much about how the global industry uses places like Cairo without saying their names. He talks about brands that manufacture in Egypt, send the pieces to Italy for a tiny last step – tags, a bit of distressing – and legally re-label the work as “Made in Italy.”

Most shoppers will never know. They’re not supposed to. Special Request doesn’t try to blow up that system; it just refuses to play that game, foregrounding process and place rather than hiding them behind a European myth. Instead, he uses Special Request “to show that these things are possible in Cairo, the place where I was born. It feels very nice to be part of this ecosystem again.”

Which brings everything back to that church.

Displaying in a showroom, or a Paris hotel, would have been the straightforward move. Instead, Tohamy chose a place that already carries ritual and weight: a 19th-century brick shell where people usually go to speak to God, or at least to something larger than themselves.

Inside St. Elizabeth’s, Special Request one-of-one pieces hang in a space that feels almost too intimate. The playlist – built over years, constantly updated while he designs – spills out into the aisles. There’s no runway, no seating chart, just people walking slowly, breathing in smoke and leather and wax, taking time. “I wanted people to feel like they’re part of this environment we’re building,” he says. “That these pieces unfold as part of a bigger story.”

Anti-fashion in his hands, isn’t about burning the system down or screaming on TikTok about sustainability stats. It’s more stubborn: one-of-one pieces instead of drops; objects instead of accessories; a launch staged like a small, strange liturgy in a Berlin church.

- Previous Article American Label Cole Haan Opens Three Stores in Egypt

- Next Article Sylwia Nazzal Designs for a Body That Demands Space

Trending This Month

-

Feb 08, 2026

-

Feb 21, 2026