Talking Identity & Inspiration With Libyan Designer Ibrahim Shebani

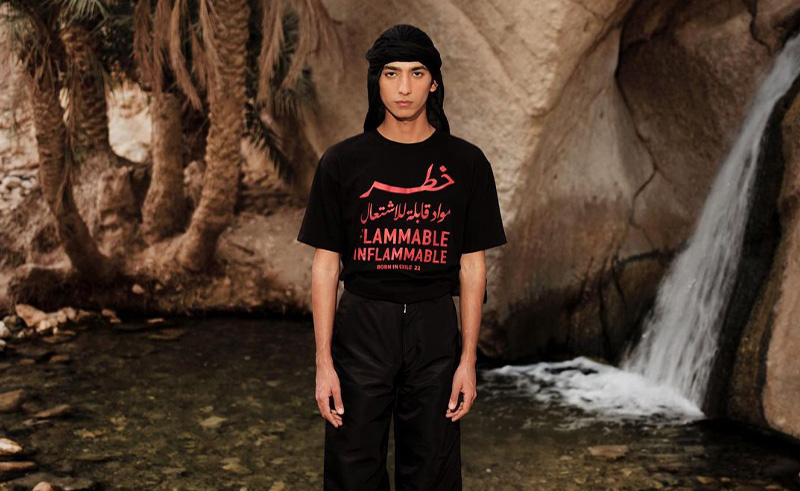

Shebani’s label Born In Exile is a sartorial investigation into what it means to be Libyan in an age of uncertainty.

In the four short years since the brand’s debut collection, Born In Exile has been selected as a finalist for the Vogue Arabia Fashion Prize and the Fashion Trust Arabia Prize, a feat not too shabby for a venture which still exists as a side hustle for Egyptian-Libyan founder Ibrahim Shebani.

-5da6e616-6596-47e6-89ce-6b4bb7ba6a56.jpg) Steeped in Libyan inspiration and Egyptian motifs, the budding designer’s collections reflect his experience of trying to locate his own cultural identity among a backdrop of instability, revolution, civil war, and the perpetually confused national identity authorities attempted to prescribe.

Steeped in Libyan inspiration and Egyptian motifs, the budding designer’s collections reflect his experience of trying to locate his own cultural identity among a backdrop of instability, revolution, civil war, and the perpetually confused national identity authorities attempted to prescribe.

-3dd1aa23-81a6-475d-a94b-785f663146f2.jpg) His story is one that actively threads culture into fabrics and sews identity politics into leather jackets and distressed denim. Amidst a flurry of work-induced sartorial investigations, I sat down with the label’s founder and head designer to hear all about its story and the vital role played by Shebani’s experience growing up inside - and outside - of Libya.

His story is one that actively threads culture into fabrics and sews identity politics into leather jackets and distressed denim. Amidst a flurry of work-induced sartorial investigations, I sat down with the label’s founder and head designer to hear all about its story and the vital role played by Shebani’s experience growing up inside - and outside - of Libya.

-e8669e63-d480-4e0e-8583-68af52739ebd.jpg) Despite not having a traditional fashion education background, and an entirely different career road-map, it seems like fashion has haunted Shebani throughout his life, lingering like a shadow of nighttime curiosities, until it eventually propelled - and inaugurated - a ravenous pursual process.

Despite not having a traditional fashion education background, and an entirely different career road-map, it seems like fashion has haunted Shebani throughout his life, lingering like a shadow of nighttime curiosities, until it eventually propelled - and inaugurated - a ravenous pursual process.

I asked him how he wound up establishing his label. “I’ll start really early on,” he began. As the youngest in his family, memories of his Cairo childhood tend to include being dragged from souq to souq in search of fabrics and dressmaking materials. His mother’s fervour for designing and sewing her own custom clothes fostered a soldered bond with clothing that Shebani carried with him over the border and into his teenage years in Libya.

“I was always obsessed with fashion, it was like the Olympics to me. For weeks I’d just watch show after show. Growing up in Libya in the 90s, there wasn’t so much around. There wasn’t much to do for a teenager. TV was the only outlet, it was like the internet today. I mean, I was glued to TV all the time.”

-a55a9441-8109-4f67-9246-7f216e2f29d0.jpg) In spite of his love of fashion, Shebani’s career took a different turn as he stepped into adulthood. “My dad is a really liberal man but when it came to fashion school he was no longer liberal. He was like, "my son is not gonna become a tarzi, you know, he is not gonna become a tailor.”

In spite of his love of fashion, Shebani’s career took a different turn as he stepped into adulthood. “My dad is a really liberal man but when it came to fashion school he was no longer liberal. He was like, "my son is not gonna become a tarzi, you know, he is not gonna become a tailor.”

Breaking into a wide smile, he laughed as he reminisced about his father’s vision for his future.

“He was born in the thirties. It was just something he couldn’t comprehend.”

Shebani unplugged his sewing machine, enrolled in architecture school, and ultimately opened up an advertising and marketing agency which prospered until 2011. Libya was hit with a revolution and a subsequent civil war, halting his entrepreneurial endeavours and forcing the company to shut down. Reifing the damages incurred, Shebani relocated to Jordan with a huge question mark hanging over his future.

“I thought, do I really want to be working in an industry I have no passion for? Or do I want to start my journey in fashion?”

Evidently, he chose the latter rather than the former and after taking a course in fashion sketching and design, he sold his car to finance his first collection, and debuted it in Paris.

Entering the fashion space as an outsider is a daunting prospect to most, but Shebani feels his unconventional route into the industry has given him a unique vantage point. “Everyone else was worried about what was cool, what was not cool, what was the ‘done thing’. I was just following my gut. I wasn’t thinking about it as a business.”

-c4a80b60-06fd-44ad-9734-89367259bc99.jpg) It was through this first collection that Born In Exile became a finalist for both the Fashion Trust Arabia Prize and the Vogue Arabia Fashion Prize. Gaining the recognition and approval of some of the business’ biggest names marked a turning point for the label. Being on the receiving end of such validating feedback from industry legends like Alber Albaz and Elie Saab confirmed Shebani’s plans to continue pouring into Born in Exile.

It was through this first collection that Born In Exile became a finalist for both the Fashion Trust Arabia Prize and the Vogue Arabia Fashion Prize. Gaining the recognition and approval of some of the business’ biggest names marked a turning point for the label. Being on the receiving end of such validating feedback from industry legends like Alber Albaz and Elie Saab confirmed Shebani’s plans to continue pouring into Born in Exile.

“I thought to myself, okay, I’m not here to play. If these industry experts are interested in your brand, there must be something really right about it.”

Born In Exile’s first collection is defined by its intricate embroidery. Over 300 years old, the complex designs are based on a traditional textile-based style found on Libyan equestrian clothing and horse tack. Shebani sought to combine very timeless silhouettes and wearable textiles with the intricate, historic appliques, fusing traditional Libyan visuality with contemporary style.

Fast forward to Born In Exiles latest collection, ‘Never Love Me Again’, and we’re met with a complete departure from the brand’s embroidered beginnings. The designs ooze with references to 90s street style and silhouettes reflecting what was in vogue in Libya during the era. Shebani explained how the bold prints and vibrant colour schemes were inspired directly by the propaganda he remembers being bombarded by as a young teen.

Take, for instance, this busy geometric print which covers a number of pieces in the collection, which was born from the outside of the tent from which Colonel Gadaffi gave many of his speeches. Green punctuates the entire collection, again a nod to the visual landscape of Libya during the time Shebani lived there. Shebani also told me about the significance of the Happy People/ الشعب سعيد T-Shirt.

He told me how the phrase ‘The Libyan people are a happy people’ was printed everywhere. “On billboards, on walls, around the markets, in shops. Which was crazy, because in reality, people were suffering.”

A standout piece from the collection is a leather, colour-blocked shell-suit-type tracksuit. Its inspiration comes from a key visual memory of Shebani’s early teenagehood.

“The tracksuit was insane. It was everywhere in the 80s and 90s in Libya because they were subsidised by the government.”

A key event informing the collection was Ghaddafi’s sudden pivot from promoting pan-Arabism to striving for pan-Africanism. Shebani told me about how this cultural U-turn left his own sense of self in disarray as well as the collective cultural identity of the nation.

“We woke up in the morning, and everything was “Africa, Africa, Africa…Libyans were kind of lost. Like are we Arabs? Are we Africans? What are we? As a 14 year old kid, you need to have an identity…I never really managed to put myself anywhere. I think everybody in my country has had an identity crisis at one point or another.”

Born in Germany, and raised in Egypt and then Libya to a Greek mother and a Libyan father, Shebani laughed as he recounted the day his parents told him and his siblings they were relocating.

“They said, ‘okay, we’re moving back home to Libya!’ I thought, ‘home? what?’ I seriously thought I was Egyptian for most of my childhood.”

It became clear as we dove deeper into the discussion that each element of the collection is a puzzle piece from Shebani’s memory of his adolescence, reflecting a period that was not only a formative time in his life, but in the broader Libyan search for a sense of collective identity.

We rounded off our discussion with one last question: how much does he feel his work as a designer is a celebration of Libyan culture and heritage, or is it more an investigation into the identity crisis Libyans suffer with?

“It’s inspired by everything that inspired my life in Libya. It is Libyan, but at the same time it’s not 100% Libyan because that just wasn’t my experience. We weren’t wearing traditional clothes, we wore tracksuits, you know! We wore denim, we wore T-Shirts, we wore what kids in Europe were wearing, and we all fought over who had the latest Nike sneakers.”

-0491c586-dcd7-4e76-bf98-4f5d6206d4f8.jpg) “The brand, from zero-to-one-hundred percent, is completely inspired by Libya. But when I say inspired by Libya, I don’t mean that it’s inspired by things that are only Libyan, but also international things that had an effect on Libya. For example, my first collection had a rock-and-roll feeling to it, because throughout the early 90s, people were only listening to rock in Libya. Everyone was obsessed with The Scorpions, Metallica, Guns and Roses, with Journey. We didn’t really have much of our own music; stuff from abroad was what we were listening to.”

“The brand, from zero-to-one-hundred percent, is completely inspired by Libya. But when I say inspired by Libya, I don’t mean that it’s inspired by things that are only Libyan, but also international things that had an effect on Libya. For example, my first collection had a rock-and-roll feeling to it, because throughout the early 90s, people were only listening to rock in Libya. Everyone was obsessed with The Scorpions, Metallica, Guns and Roses, with Journey. We didn’t really have much of our own music; stuff from abroad was what we were listening to.”

“It may not have been ‘Libyan’, per se, but in that era it really was a part of Libyan culture.”

Trending This Month

-

Jan 31, 2026

-

Feb 04, 2026